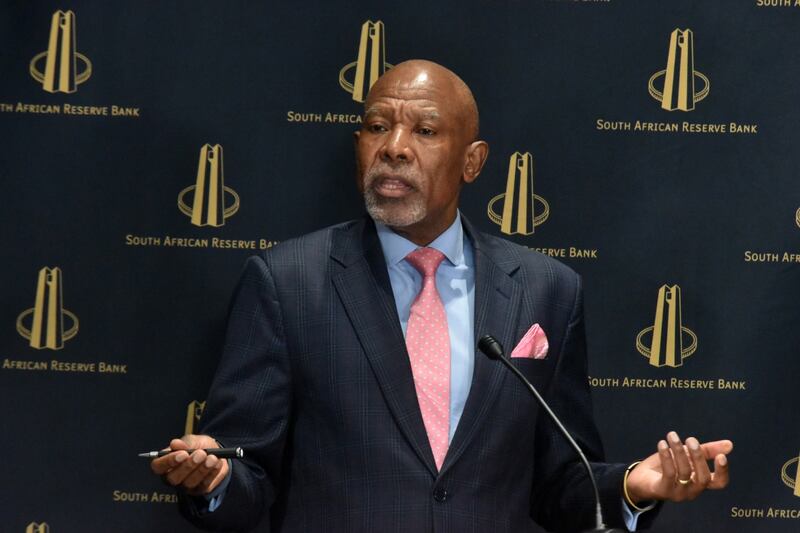

Reserve Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago has warned against loosening banking regulations that were tightened up in the wake of the 2008-09 global financial crisis, but he has opened the door to tweaking the rules to enable more investment in infrastructure.

Critics have argued that the regulations, particularly the rules on how much capital banks must hold to buffer their lending books, make borrowing more expensive and restrict credit extension. And the global Business 20 (B20) forum has recently urged the G20 to review the capital requirements to enable more investment in infrastructure, particularly in developing economies.

Kganyago said last week that the Bank’s research on the economic effect of the implementation of the Basel III regulations for banks found only an insignificant impact on economic activity, with adverse effects “modest and localised rather than large and widespread”.

And he flagged elevated macro-economic and geopolitical risks to the global financial system that could make lighter-touch regulation dangerous.

“The world is living too dangerously for us to be dismantling defences now,” he said in a keynote address at Stellenbosch University, adding that risks such as cyberattacks and money-laundering justified more, not less, regulation.

However, while the scope for deregulation was limited, there was considerable room to improve regulation and make it more effective, Kganyago said. “For example, the weights assigned to infrastructure projects in Africa remain excessively high, even though their failure rates are lower than in other jurisdictions.”

The governor did not mention the B20. But the forum has called for the prudential requirements for banks and insurers to be reviewed to help mobilise private capital for infrastructure, as part of a suite of recommendations it will make to the G20 on closing the infrastructure gap, particularly for African countries.

The B20 estimates $500bn a year needs to be added to annual global infrastructure investment of $3-trillion, with the gap for emerging markets and developing economies especially large at $68bn-$108bn.

The Basel rules require banks to hold a certain amount of capital to back their lending, depending on how risky that lending is deemed to be, in order to protect depositors. There are similar prudential rules for insurers and pension funds. The capital rules were considerably tightened after the global financial crisis to prevent the kind of risky lending that caused the US sub-prime crisis.

But critics argue that the risk weightings in some categories are way out of the line with the actual experience of default on the loans, which raises the cost of capital for development projects and limits the flow.

The B20’s finance and infrastructure task team, which this year is chaired by Standard Bank Group CEO Sim Tshabalala, said: “Current capital requirements may impose disproportionately high risk weights on infrastructure, discouraging banks and insurers from allocating capital to long-term projects. This contributes to the significant infrastructure provision gap in emerging market and developing economies.”

The task team built on recommendations from last year’s meeting in Brazil, calling for G20 finance ministers and central bank governors and the global Basel Committee on Banking Supervision to “re-explore” potential regulatory improvements.

Standard setters and regulators should review whether infrastructure should be treated as a specialised asset class, and could lower the capital banks must hold for project finance loans to levels similar to those for investment-grade corporate loans.

“Historical data shows that after five years project finance marginal default rates are lower than investment-grade global corporates, but project finance capital charges remain higher than unrated corporates,” the B20 task team said.

It also recommended reviewing prudential requirements to unlock more capital from banks and insurers working with development finance institutions that are highly rated and deemed zero risk.

Kganyago said technological advancements and financial innovation presented a double-edged sword for the global financial system, fostering greater competition and driving inclusion but potentially also encouraging increased risk taking. He listed the emergence of crypto assets and decentralised finance as another risk.

“The sustained growth rates of over 50% in some crypto assets suggest the formation of large asset bubbles,” he said.

Climate change confronted financial institutions and their regulators with another set of risks.

Would you like to comment on this article?

Sign up (it's quick and free) or sign in now.

Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.